Bernard Nevill’s acute sensibilities as a textile designer, educator and collector had a discreet yet powerful effect on more than half a century of British fashion and decor. Nevill, who has died aged 88, taught many star designers, encouraged serious applied arts scholarship, and the houses he restored and stuffed with pantechnicons of purchases – he was a hoarder of antiques – caught the imagination of people who never knew his name.

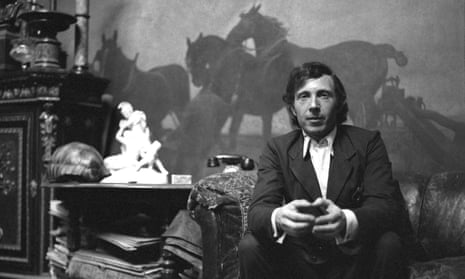

Do you remember Uncle Monty’s London home in the film Withnail and I (1987), walls layered in art, sofas smothered in exotic cushions? That was a corner of just one room in Nevill’s house in Chelsea, and the set-dressers had to shift things out to make space for the actors.

As a lecturer at the Central School of Art and Design, 1957-60, and at the Royal College of Art and St Martin’s School of Art, 1959-74, Nevill led his students to museums and galleries, and taught them about the creators of good taste over the previous century. There was no academic history of fashion then, and few publications; Nevill did original research for the information he passed on. Those students initially turned their noses up at past fashions, but Nevill was gifted at inspiring interest, and turned them on to the aesthetic vocabularies of William Morris, the pre-Raphaelites, the Ballets Russes; they became the art and craft-conscious designers, including Ossie Clark and Zandra Rhodes, of post-1965 British fashion.

A lecturer’s income hardly supported Nevill’s collecting habits, so he also designed freelance, and in 1961 was recruited to the London department store Liberty and Co as design consultant, then design director. It was hoped he would sharpen the blunted artistic edge of Liberty’s famous printed textiles. Besides knowing about the visual past, he was keenly aware of what was about to happen next, what movie, curiosity found at the Portobello Road market, or museum exhibition, would provoke creativity.

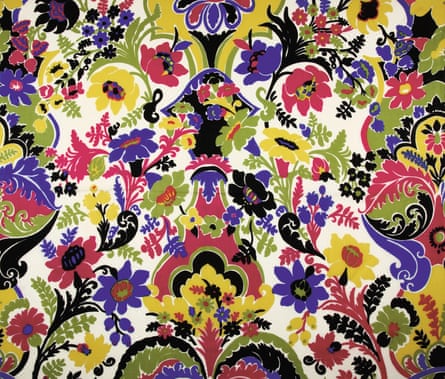

From the 1960s into the 1980s, printed textiles were a major medium for fashion in clothes and homes, a fast-changing way to enrich a simple garment or stark curtain. Nevill’s Liberty collections came out of the decorative encyclopedia in his head, referencing Hungarian embroidery, Javanese sculpture, Ottoman ceramics, 1920s stained glass and Tudor brocades in a Tate Gallery portrait exhibition; those who could not afford a single yard of the stuff still learned about then unknown cultures from photographs of the clothes.

Yves St Laurent and other Parisian houses bought his prints by the bolt, as did Nevill’s former students. He was envious that the 60s young had immediate access to fame and fortune, and he dressed as they did – only better. Although he was an aesthete, not a dandy, his pleasure was in commissioning clothes, getting a tweed specially woven or choosing a shade of suede for a shoe.

He was born in Highgate, north London, son of RG Nevill, which is all he revealed of his parents, except to admit he had rejected them for their poor taste and lack of interest in the arts. He was just as evasive about his education, saying only that he had been tutored until 15. He did reminisce about great-aunts in Kingsbridge, Devon, with whom he lived during the second world war, as their household formed his own tastes.

Ironic use of Victorian design had been a sophisticated fad since the 1920s; Nevill, though, was exposed to the genuine articles, and there was no mockery in his relationship with 19th, and early 20th, century art and design. His lifetime of addictive collecting began when those eras were going cheap in junk shops. “I am a Victorian, I know that I was born too late,” he said.

After the war, Nevill determined to go to art college, and a friend introduced him to Muriel Pemberton, who taught dress design and fashion drawing at St Martin’s, which accepted him, aged 16, as its youngest student. He later studied at the Royal College of Art, where Madge Garland was inventing formal fashion education, teaching history of dress, technical construction and an understanding of the clothing industry.

Neither institution offered a way into the business. As Nevill complained, London fashion circa 1951 had no interest in the young as customers or employees: “You had to be 44, a member of the Incorporated Society of Fashion Designers … Nobody would look at you because being young was not interesting.” He taught briefly at Shoreditch College, sketched for glossy magazines, helped with clothes for the movie Genevieve (1954) and designed unusually accurate Edwardian servants’ wear for The Admirable Crichton (1957), before being asked to lecture at Central.

After he left Liberty’s in 1972, Nevill designed textiles for another 30 years. His dress prints for Cantoni of Italy, Unitika of Japan and KBC of Germany were as personal as handwriting, while his furnishing fabrics for Pierre Frey and Boussac were often learned and sympathetic pastiches of the past. His 1981 English Country House collection for Sekers influenced the shabby, cluttered tone of 80s interiors, and many period television series since.

Nevill lamented that he would have to work perpetually at design for the money, because, besides extraordinary books, textiles, clothes, furniture and objects, he collected buildings, and architectural salvage. The first was West House, with its shy brick facade and secretive front door tucked in a corner of Glebe Place, Chelsea, bought from the Church Commissioners in 1976 for £67,000; Philip Webb, William Morris’s pet architect, had designed it in 1868 for the artist George Boyce. Nevill removed all later accretions and crammed its 15 rooms with acquisitions, many vast (his favourite word), as massivity had fetched very low prices in the 1950s and 60s. He had paid only a few pounds for gigantic bookcases and leather sofas from the Conservative Club in St James’s, and retrieved a majestic carpet, free, from a skip.

He fossicked anywhere: visiting a framer’s shop on Lavender Hill, Battersea, in 1962, to see if any interesting artwork had been discarded to release frames for sale, he spotted Frederic Leighton’s 1895 masterpiece Flaming June, priced at £60, but had to turn away as he was overdrawn at the bank. Collecting was “a disease”, he said; he told friends he had to rescue beautiful objects even when he had no use for them, as he wanted to save them from death.

The location hire fee for Withnail and I funded his collections, too. Nevill loathed the film as being “too near the bone”; its director, Bruce Robinson, and stars tried to work when Nevill was out shopping, as he was hungry for company and fussy about props. West House counted as his town house; in 1977 he had also bought a country house, a half-ruined stable block surviving from centuries of demolition and rebuilding on the Fonthill estate in Wiltshire. Restoration was never finished there, or at West House, since Nevill’s excitement was in acquiring, planning, planting and rearranging. Another delivery of architectural salvage was forever scheduled: carved staircase, marble fireplace, fragments of a swimming pool.

When Nevill fell ill at 80, his accumulations were released back into the world. West House sold for over £20m in 2011, and most of its contents were auctioned, with special catalogue mention for those in Withnail and I. Then he parted with Fonthill and took only the most perfect possessions to a new home, a flat in Cheyne Walk, Chelsea. Crates of wonders were parked in various places until his death.

He was didactic, opinionated (seldom wrong) and entertaining, and knew more than anybody about the secret lives of things.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion