Edinburgh Art Festival reviews: Leon Morrocco | Barbara Rae | Duncan Shanks | John McLean | Raphael

Leon Morrocco: Long, Road Home, Royal Scottish Academy, Edinburgh *****

Barbara Rae: Lammermuir, Open Eye, Edinburgh *****

Duncan Shanks: The River Bank, Scottish Gallery, Edinburgh *****

John McLean: Flare, Fine Art Society, Edinburgh ****

Raphael: Magister Raffaello, Dovecot Studios, Edinburgh ***

Advertisement

Hide AdA remarkable generation of Scottish artists came of age in the 1960s. Now in or near their 80s, it’s time to retire perhaps, except that artists generally don’t retire and a group of current shows suggests they just go on getting better. Leon Morrocco is celebrating his 80th birthday with an extensive show at the RSA. Duncan Shanks, who was born in 1937, has an equally extensive show of recent work at the Scottish Gallery, while Barbara Rae, who has a significant birthday next year, has a show on the same scale at the Open Eye. John McLean, too, belongs to this generation. He was 80 when he died three years ago, but the show of his work from the 70s and 80s is smaller and more retrospective in mood than the others. In a quite different time span, celebration of the 500th anniversary of Raphael’s death in 1520 was knocked back by the pandemic, but is now being marked by a digital show at Dovecot.

Of the four contemporaries,McLean was always a committed abstract painter. He took his cue initially from the Abstract Expressionists and the later generation of North American abstract painters, but developed a lyrical style that was quite his own. Landscape inspires the work of both Shanks and Rae, however. The drawing in Shanks’s sketchbooks at the Scottish Gallery is vivid and direct. Though not on view at the Open Eye, Rae’s sketchbooks are equally striking, recording with dramatic immediacy whatever she wants to put down for use in her painting. Nevertheless the way both these artists paint has clearly been influenced by the same post-war abstract painting that set McLean on his chosen course.

In contrast to these three, however, Leon Morrocco’s art is concrete. His drawing is beautiful, but does not go through a major metamorphosis as it informs his painting. He composes and reorganises what he has seen with great skill, building out of his observations subtle and complex compositions, often on a very large scale. Morrocco was taught initially by his father Alberto Morrocco, a gifted draughtsman and a pupil of James Cowie. Leon has inherited his father’s gift undimmed. His lucid and powerful drawings are a delight. Their discipline brings a sense of order to his painting that allows him to work successfully on a really grand scale. Community Garden, Melbourne, for instance, is five metres across. The picture’s subtitle, The Morning after the Night Before, reflects the human comedy that often enlivens his work. Morrocco’s travels are the matter of his art, ranging from Italy and Greece to India, North Africa and Australia where he lived from 1979 to 1992. The title of his show, Long Road Home, suggests maybe he has travelled enough, but his recent work is of the Alpes Maritime, the mountains behind Nice. The finale to his show is a group of four paintings, all on matching, nearly square canvasses and looking straight into these rocky mountains above green fields and the red roofs of the little towns that huddle at their feet.

Barbara Rae has also been peripatetic. She recently travelled several times to the Arctic, for instance, to produce a remarkable group of paintings. She couldn’t travel in the pandemic, however, and so turned to the Lammermuir Hills in winter. They are within sight of Edinburgh, but are steep and high enough to have occasional snow six months of the year. They are not so high but are nevertheless such a formidable barrier that only the Romans ever put a road across them. It is now the A68. Rae has produced a sequence of really dramatic paintings. In them, the hills’ vertical landscape rises out of the fertile fields of East Lothian to the line of summits against the winter sky. Her chosen format, like Morrocco’s mountain paintings, is a nearly square canvas. The Lammermuirs are wild, but also have marks of the human presence over millennia in tracks and archaeological remains, and the shelter belts, gates and fences of hard won fields on the lower slopes. Rae brings all of this into her imagery. Her pictures are dark, but winter is not colourless in Scotland and she explores all the tints and hues and the drama of light and shadow. As she does so, her pictures, although still landscapes at one level, work as abstractions at another. It is a remarkable achievement to have harnessed the language of abstraction to create pictures of such powerful mood informed by a real sense of place.

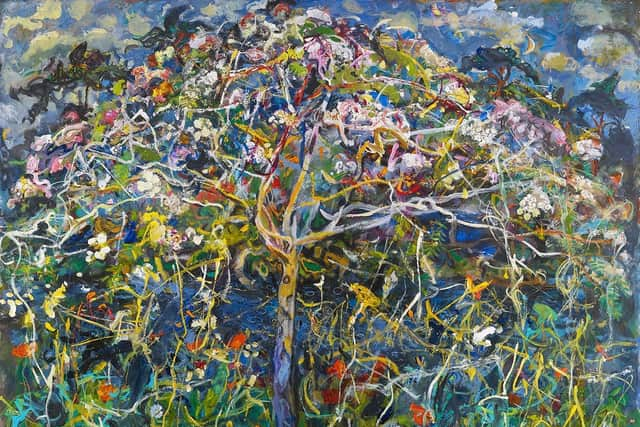

Duncan Shanks’s show is called The Riverbank and is also dedicated to an intense exploration of the drama and contrasts of one particular place. The Clyde flows past his house and the riverbank is his garden. Whereas Rae stands back, Shanks is often almost entangled in the vegetation that clothes the steep banks of the Clyde as he looks down at in flood, or up at the sun or moon through a screen of trees and foliage. We see all that, yet what we are equally conscious of is the picture itself, the energy on the surface of layered runs of paint and colour. The acrylic he uses can be quite liquid and yet retain body so the painted surface is tangible. These are really abstract, physical paintings before they are pictures of something seen, although they are that too. It is quite remarkable how they look like Jackson Pollock’s abstractions yet also carry all the artist’s intense sense of place and of the energy and animation of nature. He and Rae have both both done something remarkable, harnessing the vital language of abstraction to create pictures that nevertheless engage poetically with our experience of the world around us.

John McLean really started with Pollock when in the mid-60s he shifted from a kind of social realism to free gestural painting, but he moved on to create his own formal language. In his show, Flare, at the Scottish Gallery, Thunder Bay from 1976 shows how he was by then already using colour, gesture, texture and differing depths of transparency to create a poetic language as abstract as music. He was a master of colour. Even on a small scale his pictures sing. That is really the only word for the joy in his canvasses. They sing and dance, an analogy that he liked to make himself.

Advertisement

Hide AdWhat would Raphael have made of all this? Painting has certainly taken a long road since his time. It is also true that he has been somewhat overshadowed. He was once held up as the model for all artists, but tastes changed. Michelangelo’s heroic struggle is more in tune with the times than his fabled serenity. The survey of his work on screen at the Dovecot Studios is a good reminder of why he was once so highly rated. Michelangelo’s rival, he designed the tapestries that hang in the Sistine Chapel beneath its more famous ceiling. The main purpose of this display is as an introduction to a tapestry made from a detail of one of the cartoons Raphael made for the Sistine series. Acquired by Charles I for the Royal Collection, the cartoons are now displayed in the V&A. The detail has been woven by three Dovecot weavers from the cartoon of the Miraculous Draught of Fishes. The detail is of two fishermen leaning down to pull their net out of the water. Evidently techniques have changed and the new tapestry does look distinctly modern, but it is wonderful that it has been done at all.

Leon Morrocco until 28 August; Barbara Rae until 27 August; Duncan Shanks until 27 August; John McLean until 27 August; Raphael until 24 September